What kind of move?

What kind of move?

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Writers use all sorts of fancy names to describe different kinds of moves. In a large game collection, Savielly Tartakower cited more than a dozen types of sacrifice. He gave each type a name, such as 'vacating sacrifice.'

These distinctions may make for entertaining reading. But they aren't very helpful If you try to use them as a checklist during a game - and look for an 'irruptive sacrifice' or a 'rolling up sacrifice,' whatever they are - you'll just waste your time.

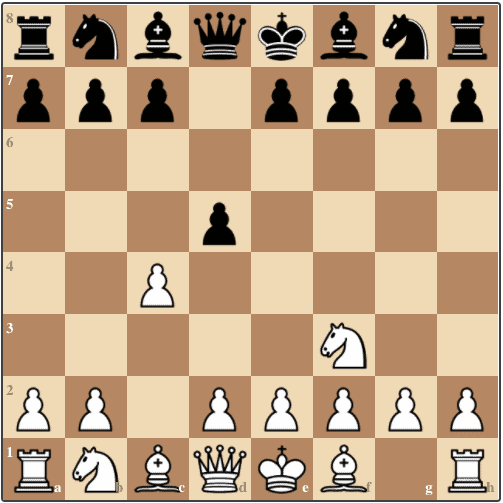

However, it is useful to look at the basic kinds of middlegame moves. We can roughly identify four:

(a) Tactical moves. These moves make checks, captures, sacrifices or threats, or they respond to checks and threats. These are forcing or forced moves.

(b) Repositioning moves. They change, and hopefully, improve the placement of one of your pieces or worsen the range of an enemy piece.

(c) Exchanging moves. They offer, initiate or complete an exchange.

(d) Moves that change the pawn structure, that is, moves that are significant advances or captures

Of course, there are some moves that fall into more than one category. A knight advance that makes a threat can be both tactical and repositioning. A recapture of a piece with a pawn will change the pawn structure while completing an exchange.

But the point here is that TMI (too much Information) is a more manageable beast if you appreciate that you are essentially dealing with these four types - not 17 or 23 - and that some of them occur much more often than others.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Which ones occur most often?

Well, if we think of the middlegame as lasting from roughly move 21 to move 40, statistical surveys of master tournaments show that repositioning moves are the most common. In second place are tactical moves. These are the moves you will be playing most often.

On the other hand, trading moves and changes in the pawn structure are relatively rare because

(a) you can only swap seven of your pieces in a game and

(b) once a basic pawn formation is set in the opening, it doesn't change very much. The significance of these moves lies in their permanency. A trade or a pawn push cannot be taken back. And because they so often change the evaluation of the position, they deserve their own method of study.

You can work on your skill at trading and pawn pushes by looking, once more, at master games with a special emphasis. After move 15 you should stop whenever a piece is traded or a pawn is pushed. Don't move on - or click on - until you can explain why the move in question makes sense. If a player initiated the trade, figure out why. Was the trade forced? Does an exchange favor him? Certain players, such as Fischer, Anand and Capablanca never seemed to have bad pieces - because they exchanged a potentially bad one off long before it became bad. Their games deserve your attention.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Andrew Soltis, Studying Chess Made Easy

No comments:

Post a Comment