Teach Yourself Better Chess...Part One

Teach Yourself Better Chess...Part One

In 1997, International Master Bill Hartston published a book called Teach Yourself Better Chess. Its goal was to delve a little more deeply into the principles of good chess. He explained the ideas behind the elementary rules of chess and introduced the reader to what makes up good judgment and intuition in chess. Here are some of Hartston’s principles and advice.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

First, try to calculate the calculable. One must calculate the technique to calculate forced moves such as captures and heavy threats through the end, even if it is 10 or 20 moves deep. He points out that there are two types of thinking going on: precise thinking (tactics) and fuzzy thinking (strategy). Only when you have calculated the calculable and no clearly advantageous continuation emerges, it is time to move into the fuzzy thought of looking for the most promising path through the forest of incalculable possibilities.

Always look one move deeper than seems to be necessary. Just when the forcing moves appear to have come to an end, there may be a subtle move that puts a completely different complexion on the position. The tactics do not always end when the captures and checks run out. You also must train yourself to look for winning combinations for your opponent also. Sometimes we stop analyzing because there is no more forcing moves such as check or capture. If your opponent has no important threats, you may have a spare move that would help your position, which may force a winning position.

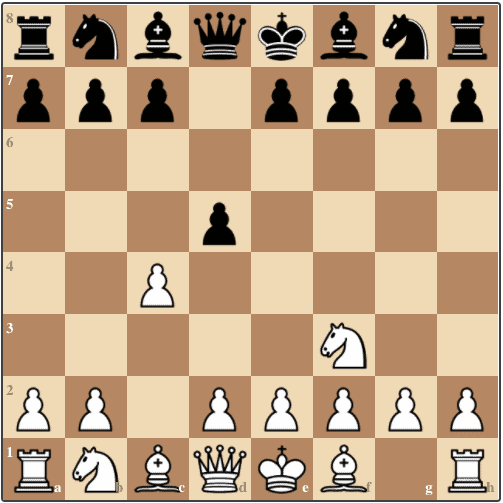

Control of the center is the key to flexibility. In the early stages of the game, the center is the most important part of the board. A piece, especially a knight, can influence play on both wings from a central outpost. The side that controls the center can easily switch his forces from one wing to another. Try to occupy the center with pawns. Advance them systematically to enable pieces to occupy the squares behind them.

Know when to exchange pieces. In general, it is likely to be advantageous to exchange pieces when you have more pawns than your opponent, everything else being equal. An extra pawn increases in value the fewer pieces are on the board. If you have a cramped position, swapping off one piece can create much-needed maneuvering space. The most important thing, however, is to think about the pieces that will remain on the board before you exchange any pieces. You want to make sure you are not losing a crucial piece that is needed in the game. Weak players usually assess a position by counting the captured men. Strong players consider only the men remaining on the chess board. Before exchanging, ask yourself, “Will he miss his piece more that I’ll miss mine?” Many games have been lost because the loser permitted the exchange of a vital defensive piece, or allowed the attacker to simplify into a winning endgame.

When it comes to a bishop and pawns, put your pawns on the same color as your bishop on the flank where you are defending, but on the opposite color on the side where you plan to attack. A bad bishop can be a good defender.

If there is active play happening on both wings and no pawns are blocking the center, then a bishop is stronger than a knight. If the central pawns are blocked and look like they will stay that way, exchange your bishops for knights. If you are playing with a bishop against a knight, try to exchange central pawns, and create something to think about on both wings. A bishop may simultaneously influence play on both sides of the board. A knight is too slow to influence both sides of the board. The bishop is much stronger than the knight in an endgame where the players have passed pawns on opposite sides of the board. The knight has to choose whether to attack or defend.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

No comments:

Post a Comment