Teach Yourself Better Chess...Part Two

Teach Yourself Better Chess...Part Two

In 1997, International Master Bill Hartston published a book called Teach Yourself Better Chess. Its goal was to delve a little more deeply into the principles of good chess. He explained the ideas behind the elementary rules of chess and introduced the reader to what makes up good judgment and intuition in chess. Here are some of Hartston’s principles and advice.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

There are two good reasons for castling. You don’t want the king caught in the center, and you want to connect the rooks and bring one ready to occupy a central file. However, castling is not just a king move. If your rook is doing a good job on its original square, such as supporting an advance of a rook pawn or occupying an open file that can attack the enemy king, then it may make more sense to leave it where it is and not castle at all. When the center of the board is safe, it can be a good strategy to leave the king there until the moment comes for the cornered rook to get in the game.

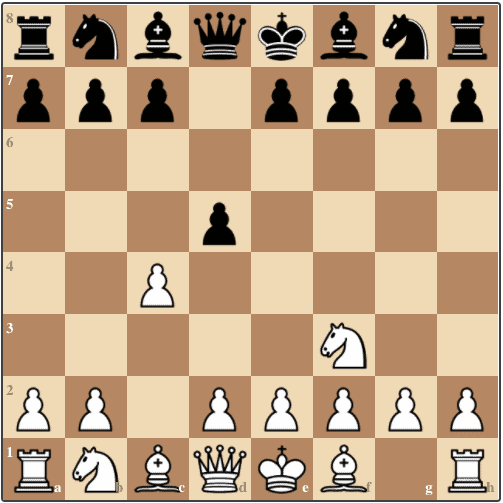

Your aim in the opening should be to get your pieces into play as soon as possible, so that they can cooperate with one another rather than stepping over each other. If a piece takes more than one move to reach its most effective square, then that is OK. What is important is to avoid wasting time and tempo. Don’t move a piece to one square, then change your mind and move it to another square on the next move. Don’t spend two moves doing something that could have been done in one move, while your opponent has made two useful moves in reply.

Bishops are best played when they are on the long diagonals, the ones from corner to corner. When a player plays g3 (or b3), then Bg2 (or Bb2), we refer that as the bishop in fianchetto (some say fianchettoed bishop). Fianchetto is an Italian word meaning wing or flank. When not in the corner, every bishop has one major diagonal and one minor diagonal. It is best that the major diagonal is as long as possible. The bishop looks forward in attack while glancing backwards in defense.

In most positions, there is no such thing as a correct plan. There is only a flexible set of options ready to put into operation according to the options selected by the opponent. You have to satisfy yourself that there is nothing you can do to win the game immediately, nor any defensive task that demands immediate attention. After that, you then ask yourself “Where would I like my pieces to be in a few moves time?” That’s your goal or planning in chess.

When you have found a good move, play it! Just make sure it is as good as you think. Strong players always think a good deal before playing an “obvious’ winning move. If it is really a winning move, you can even spare the time to look at every legal replay you opponent has at his disposal.

Think strategies when it is your opponent’s move; think tactics when it is your move. The constant interplay between strategy and tactics is an essential part of good thinking. After your opponent makes a move, ask yourself “Has my opponent’s last move left him open to a killer punch? If not, does it threaten anything that demands immediate action?” After that, look at the static features of the position – the pawn formation, the weak squares, the safety of the kings, the potential endgame advantages, and other such elements that lead to the formation of a general strategy.

Most of the time, a rook placed on an open file is the best place for a rook. That is true when the file offers the rook a chance to advance and attack enemy weaknesses, or when conceding the file to the opponent’s rooks would let him do the same thing. Sometimes a rook does better behind a not-yet-open file, in preparation for a predictable opening of the position. Also, a rook is very good behind an advancing pawn. The rook supports the pawn’s advance and the advancing pawn creates more space for the rook.

No comments:

Post a Comment